PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayAmong the autopsy reports that made my heart skip a beat was Hannah Rose Moody.

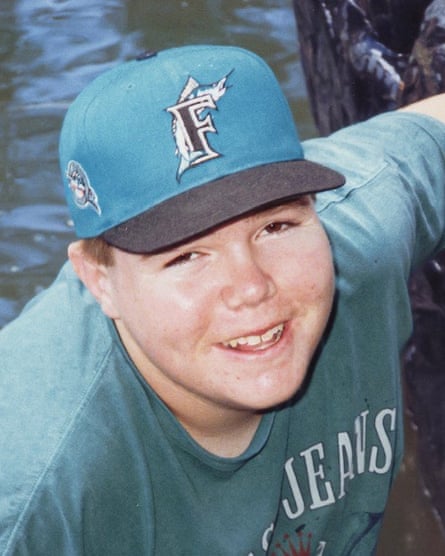

One morning last May, the 31-year-old set out on a favourite desert hike near her home in Scottsdale, Arizona. It was already 91F (33C) when she set off. On Instagram, she told her 50,000 followers: “Conquering this trail as a last hurrah before summer hits 🥵☀️… I have like 5 gallons of water with me don’t worry 😅.”

By midday, the temperature had climbed above 100F (38C).

When she did not return, friends raised the alarm. A search team found her the next day, less than 100 yards (91 metres) from the parking lot.

According to the infrared thermometer used by the death investigator at the scene, Hannah’s body registered 142F (61C) after a day in the desert sun. Inside her backpack were three empty water bottles, packets of fruit snacks, sunscreen and a fully charged portable phone battery. Her phone, however, had no power.

Heat exposure killed Moody a week before her 32nd birthday. She was a waitress and an aspiring social media influencer who regularly posted about her Christian faith and passion for hiking. Her death was ruled an accident by the Maricopa county medical examiner.

“Had she left a couple of hours earlier, she would have probably been fine … but when you’re 31 you feel invincible,” said Hannah’s mother, Terri Moody. “The irony is that she always wanted to inspire people, and in her death she finally went viral and has probably made a difference.”

Hannah Moody’s case was not unusual. Her story is one of hundreds, each hidden in the dry language of medical examiner reports.

This year alone, she is among more than 530 suspected heat-related deaths in Maricopa county, home to Phoenix, America’s fifth-largest city. This year’s death toll comes on top of another 3,100 confirmed heat-related fatalities over the previous decade.

Wanting to understand who those deaths represent, I spent the summer reading those hundreds of autopsy reports and speaking with the families left behind.

The autopsy and investigative reports, which I obtained from the medical examiner’s office using the Freedom of Information Act (Foia), provide a window into each person’s life and death. They note where the person was and what they were doing when they died, list medical conditions, alcohol or drug use, housing status, and whether they had air conditioning or electricity if they died indoors. About three-quarters died outdoors.

I already knew from years of reporting in Arizona that some groups are especially vulnerable, including unsheltered people and those struggling with addictions. But combing through these cases revealed other, more common risk factors – such as being overweight and living with dementia. Heat overworks your heart, confuses the brain, shuts down your organs, but rarely causes death directly. It is far more common for heat to exacerbate pre-existing conditions such as diabetes, asthma and heart disease.

All the reports were clinical, yet hard to read emotionally, because what they reveal is devastating. They show lives cut short in ordinary, preventable ways – the air conditioning unit that broke, the immigrant who collapsed after the border crossing, the single mother who never woke up in her car.

Take Brett George Westbrook. Last summer, the 65-year-old’s body was found decomposed in his trailer after friends noticed he had missed his daily walk for four days and called police for a welfare check. Westbrook had high blood pressure and chronic alcoholism, and had been taking cold showers to cool down since his AC broke six months earlier. According to the autopsy report, a few days before the heat killed him, he had told relatives that he had failed to fix the AC himself, and it was too expensive to get repaired.

Amber Marie Goodwin-Arnold was found dead in her car, where she had been living for several weeks with her two children after moving from Illinois. Her children woke up and found their mother, who was 33, unresponsive in the driver’s seat. They went to get help, but it was too late.

Maria Del Carmen Diaz Rojas, a 24-year-old undocumented immigrant who had just made it over the border, was found three days after she fell sick and was abandoned in Phoenix by smugglers. “She was found decomposed at a construction site, lying on her back fully clothed … her body temperature was 144 degrees Fahrenheit. There was no food or water in her belongings and her body was fully exposed to the sun,” the report says.

CAUSE OF DEATH:

Probable environmental heat exposure

MANNER OF DEATH:

Accident

HOW INJURY OCCURRED:

Smuggled individual found in high environmental temperatures without water or shade

And earlier this year, Michael Nez, an Indigenous man from the Navajo nation with a history of alcohol addiction, was found slumped and unresponsive at a bus stop. “Witnesses report he was in the same position for many hours. High temperature on the day of discovery was 104 degrees Fahrenheit,” the medical examiner’s final report says.

What it did not say – but the investigator’s case notes did – was that a local fire crew, who also serve as paramedics, were among those to witness Nez “as they passed by a few times to slowly slump lower and lower on the bench throughout the day”. When they finally called in a welfare check he was already dead. When the investigator arrived an hour later, Nez’s body was lying in full sun and measured 138F.

I could not reach his relatives, but an obituary described Nez as a punk rock musician who found solace in long walks and the natural world, and who “will be deeply missed by all who knew him”.

After weeks of combing through case files, certain deaths stayed with me.

I have covered violent, traumatic deaths for nearly 20 years, but heat fatalities felt different – not sensational, just painfully ordinary and entirely preventable. That ordinariness made them seem cruel.

These were people with the same medical conditions and financial struggles millions of Americans live with. None of them had to die that day.

That preventability is what makes the bigger picture so shocking: heat is the leading weather-related cause of illness and death in the US – a toll made worse each year by human-driven global heating.

When I visited Phoenix, the city was in the grip of a grueling heatwave: temperatures hit at least 110F on 13 out of 14 straight days. Last summer, the city endured a record-breaking 113 consecutive days at or above 100F, shattering the previous record. The damaging effects of heat on the mind and body are cumulative, and we only begin to recover once the temperature drops below 80F. Last year, the temperature did not fall below 90F on 36 separate nights. (Before 2020, Phoenix had never logged more than 15 such nights in a year, according to the National Weather Service.)

Even these extremes do not capture the full toll. The official heat death count for the US almost certainly underestimates the true toll, thanks to inconsistent reporting standards, limited resources for investigations, and the fact that heat usually kills indirectly by worsening existing conditions that are often listed as the main cause of death. Without understanding the circumstances of a death, the role of heat is likely to be overlooked and therefore not counted in the death toll.

“No one dies from a heatwave,” Bharat Venkat, director of University of California, Los Angeles’s heat lab, told me. “The way in which our society is structured makes some people vulnerable and others safer.”

In other words, it is not just the heat. It is inequality – who has access to shelter, healthcare, money and social support – that often determines who lives and who dies.

One recent large study from China found that heatwaves significantly increase the risk of death caused by Alzheimer’s and other dementias. Being confused and disoriented makes it harder for people to perceive the threat and therefore more susceptible to dehydration and heatstroke. High temperatures may also exacerbate the symptoms of neurological diseases, while commonly prescribed medications can interfere with the body’s ability to regulate temperature.

This does not bode well for the future. Almost 7 million older Americans currently live with Alzheimer’s, which is projected to more than double to 14 million by 2060.

How bad the heat gets depends on whether the world takes radical action to change course and stop burning fossil fuels. But by 2050, climate scientists warn that dangerously hot days and nights will occur far more frequently across the US, while heatwaves will last longer, affect more of the country, and become more severe.

Behind every death report was a person with a life, someone with friends, hobbies, and hard times. I needed to understand who each person once was to truly understand why the heat cut their life short.

To get past the clinical data, I followed the trail in the medical examiner’s case notes, which often included the first thread of a story: a neighbor who called in a welfare check, or the name of a surviving spouse.

I made hundreds of calls which in many cases came to nothing – either the numbers were no longer in service or belonged to someone else. Some relatives did not want to speak with me, but others were grateful for an opportunity to talk about their loved one.

Kenneth Markwood was found in his back yard, his body covered in ants, on 12 May 2025. He had wandered outside around 10am while his wife, Michelle, and stepson, Craig, were still in bed. He was smart, a retired accountant, a good dancer and keen golfer but had become increasingly withdrawn and confused over the past six months. He was 82 and had dementia, as well as chronic conditions common among older Americans: type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Michelle, 80, told me that Kenneth had started getting distressed because he stopped recognising the house, and would ask to go home to downtown Phoenix where he had lived as a young man. Michelle would drive him there and they would sit in the car until he forgot why they had come. She never let him go out alone, but the back door was not locked because the yard was protected by a 6-ft-high fence.

Kenneth had been out in the yard for less than an hour when Craig found him. It seemed as if he had stumbled and fallen, and was unable to get up. He was still breathing but barely responsive when the paramedics arrived. His body temperature was 107F, so hot that his organs were shutting down. The normal core temperature for older people ranges between 96F to 99F, but the body’s ability to control temperature decreases with age.

He was transported to a hospital where he was diagnosed with heatstroke. Kenneth never regained consciousness and was discharged to hospice care, where he died eight days later.

Kenneth’s death was recorded as accidental.

“My husband was extremely smart and interesting, and even after 45 years together I was still in love with him,” said Michelle. “He’d lived in Arizona since he was 15, I can’t believe the heat killed him. I hate the way that he died.”

Globally, heat killed an estimated half a million people each year between 2000 and 2020, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), with deaths among older people rising by about 85% during that period. But it is also cutting short the lives of healthy young people – some who were out having fun like Hannah Moody, others who were in the middle of their working day.

Michael Dean Sheppard was born and raised in the Phoenix area, and had worked with his dad as a landscaper for almost 30 years. On 21 July 2024, they began work early to avoid the worst heat, arriving at a commercial business for their second and final job for the day by 9am. Michael was raking leaves at the back of the property –his dad, Harry, out front – when he felt unwell and took a 20- or 30-minute break in the van with the AC on and a Gatorade. A short while later, Harry went to check on his son as he couldn’t hear Michael’s leaf blower. He found Michael lying face down, unresponsive on the ground.

He rolled his son, who was 6ft1in and 336lb, on to his back and initiated CPR. But Michael, 46, was gone. According to the autopsy report, Michael was obese and had bipolar affective disorder. Heat can exacerbate mental distress including mood disorders, and some commonly prescribed medications interfere with the body’s ability to regulate temperature.

There was something about the silent leaf blower that made me teary, and I imagined how awful it must have been for Harry, 74, to find his son on the ground.

It took a while to connect with Michael’s family. The number I found for the Sheppard family home was no longer in service, so on one baking hot afternoon I visited unannounced. Harry was caught off guard, and his wife, Michael’s mother, Susan, had just been admitted to a care facility. But he gave me his mobile number and said to call. I tried multiple times, to no avail. A couple of weeks later, Harry picked up. His daughter had confirmed my credentials online, and Harry was eager to tell me about his son.

Michael, he said, was a “fine Christian young man who loved Jesus”, said Harry, who wept throughout the call. He loved food – especially spare ribs – and was a huge fan of Tom Brady, the football quarterback. He watched as many basketball, baseball and football games as he could, and hosted Super Bowl watch parties.

“He died of heat exhaustion, his heart gave out,” Harry said. “God forbid this happens to anyone else, a piece of my heart is gone for ever. Michael was more than my son. He was my right-hand man. It’s always been hot here, but not like this. I haven’t worked a single day since he died.”

Harry’s grief is still so raw that he cannot bring himself to scatter Michael’s ashes.

According to one recent study, heat is responsible for as many as 2,000 worker deaths each year in the US, and at least 170,000 work-related injuries. This makes heat one of the most dangerous conditions facing workers in the US, and its effects are far higher than the official counts.

There is no federal standard to protect workers from deadly heat, perhaps because it is the most vulnerable – immigrants, incarcerated people, and people of color – who disproportionately make up the labor force in agriculture, construction, landscaping and manufacturing.

America does not have a reliable way of counting heat deaths. The nation’s 2,000-plus coroner and medical examiner offices follow no single protocol, and in many cases, whether heat is listed as a factor depends entirely on the experience and qualifications of who certifies the death.

Maricopa county, for example, is considered the gold standard for investigations that are carried out by experienced forensic pathologists, yet it has recently come under fire for allegedly undercounting heat-related deaths, specifically among the transient or homeless community.

In 2024, the medical examiner’s office reported 608 confirmed heat deaths. But it also kept a separate tally of more than 800 deaths among homeless people, of which 35% were classified as heat related. But dozens of people who appeared to have died in high temperatures were not counted as heat deaths, according to a local ABC15 investigation.

I came across one such case, which I shared with Dr Christina VandePol, a retired coroner and physician from Pennsylvania, for an independent opinion.

In April 2024, Tresor Banani was found dead in an alleyway close to the apartment from which he had been evicted two weeks earlier. A suitcase with some clothes, medications and hygiene products was found next to his decomposing body, alongside empty alcohol containers. He was 37 years old, and had a history of hypertension and alcohol use.

The medical examiner’s final report said:

Based on the above findings, reported circumstances of death, and all other investigative information received to date and as available to me, it is my opinion that the cause of death is alcohol use disorder with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease as a contributing factor. The manner of death is natural.

But the preliminary investigative report, which includes case notes and details from the scene, states that “the cement in direct sunlight measured 122F on an IFR [infrared] device. The high temperature recorded over the previous 48 hours was 99F.”

“I would have probably certified this as death due to excessive heat exposure with alcohol use as the contributing factor,” said VandePol. “He didn’t die while drinking in his air-conditioned apartment. It’s likely that the heat tipped him over and was the final factor … I see no reason that exposure to environmental heat should be excluded as, at the least, a possible or probable factor in his death.”

A Maricopa county spokesperson said Banani showed no signs of dehydration which is often seen in heat-related deaths, and no audit of the transient death list had been conducted since media reports of alleged undercounting.

I tracked down Tresor’s brother, a physician in California, who was shocked to hear from me. He said that his brother was a maths teacher who had been fired a few months earlier. He knew Tresor had been going through a hard time, but had been unaware about the eviction and alcohol use until his death. His brother wondered about the heat too, and even hired a private investigator to try to answer questions the family had about why Tresor died in such sad circumstances. He seemed relieved to have more information, but after that did not want to speak with me further.

Amid increasingly brutal heatwaves, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created a comprehensive standardised protocol to help coroners and medical examiners ascertain the role heat played in someone’s death and improve reporting, yet no one is mandated to use it. (Maricopa county said they already collect all the data recommended, if available).

“If we don’t fully account for heat deaths, we are missing opportunities to implement life-saving public health interventions. But if we faced the reality of how many Americans are dying from heat, maybe we would have to do hard things like provide access to cooling and tackle the climate crisis,” said Venkat, the heat researcher from UCLA.

In many developed countries, epidemiologists estimate heat fatalities by calculating excess or unexpected deaths during a severe hot spell. For instance, the 2022 heatwave in Europe led to almost 62,000 heat-related excess deaths, while this summer 16,000 more people died prematurely. While this methodology does not provide us with details about why or how people died, it does give a much clearer picture of how many lives extreme heat is cutting short.

The US, for some reason, chooses not to know.

“I think it would scare people if the real numbers were available,” VandePol added. “But we’re all gonna feel the impact of heat-related deaths and morbidity in the years to come, so the sooner we stop underestimating the threat and start figuring out how to mitigate what’s going to happen, the better off we will be.”

“I hate the heat,” said Terri Moody, whose daughter Hannah died hiking. “It doesn’t matter if you’re young, fit and experienced, the heat doesn’t care.”

14 hours ago

11

14 hours ago

11

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·