PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayIn March, as Cyclone Alfred roared towards the south-east Queensland coast, the bayside suburbs of Brisbane were treated to a rare cold-water visitor. A shy albatross was spotted offshore, opposite a fishmonger in Sandgate. A couple of days later, what was likely to be the same bird flopped into a front yard of nearby Banyo, exhausted.

The bird was taken into care by seabird rescuers Paula and Bridgette Powers, better known as the Twinnies. “Banyo Alfred”, as they named their bird, was exhausted, emaciated and riddled with lice, as were hundreds of other birds the twins treated in the cyclone’s wake. Two months later, Alfie was well enough to be released back out to sea.

Which, on the face of it, sounds like a good news story. But let’s come back to it.

The shy albatross, Thalassarche cauta, is the only one of the world’s 22 albatross species to breed in Australia: on the fittingly named Albatross Island, off north-west Tasmania, and Pedra Branca and Mewstone, two stacks off the island’s south coast. All three spots are remote; the last two are impossible to access.

It is a majestic bird, with a wingspan of more than 2.5 metres. It is not at all shy, despite its name. It was once thought to avoid boats – but I have spent a lot of time at sea* and have never seen a shy albatross knock back a free feed. Thalassarche, the scientific name for the genus to which it belongs, is much better. It is derived from the Greek and translates as “sea commander”.

If you live in southern Australia (anywhere from Sydney to South Australia, including Tasmania) it’s not that hard to see a sea commander. Just wait for a good southerly blow in the middle of winter, rug up, pick a spot on any decent headland in the teeth of the gale, and you’ve every chance of seeing one wheel by on the wind.

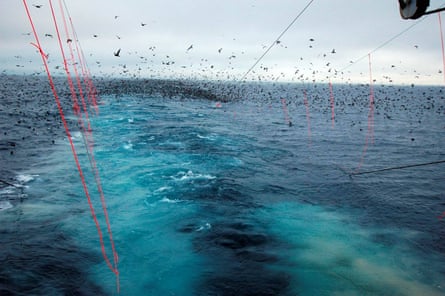

For most of us, though, albatrosses are more like myths. They usually live far offshore, familiar only to the crews of fishing trawlers. They are harbingers of both good and ill-fortune. To harm an albatross is a grave sin in seafaring lore, as depicted in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, who is cursed after shooting an albatross with a crossbow:

And a good south wind still blew behind,

But no sweet bird did follow,

Nor any day, for food or play,

Came to the mariner’s hollo!

And yet, of the 22 species of albatross, 15 are considered threatened.

Things went particularly badly for the shy albatross after the arrival of Europeans in Australia: after the discovery of Albatross Island in the late 1700s, an estimated population of 20,000 pairs was reduced to just a few hundred nests by the early 20th century, due to egg collecting and feather harvesting.

Those practices have long since been banned and numbers have recovered to about 30,000 mature individuals. But it’s still considered near-threatened, due to three related issues that affect all the world’s albatrosses, and many other seabirds: longline fishing, global heating and their protracted breeding biology.

Albatrosses naturally live long, mostly solitary lives. After leaving the nest, they remain at sea for at least three years, not maturing sexually until they are around seven. Dr Yuna Kim, BirdLife Australia’s seabird project coordinator, tells me that finding a partner is hard work: “They have to be really good dancers!” she says. “It’s very cute, but such an effort for them.”

Yes – juvenile shy albatrosses spend several summers learning to dance, a synchronised pattern of bowing, bill clattering and other smooth moves. The ritual is thought to strengthen pair bonding: when pairs reunite after the long winter, they continue to dance for each other before settling down to breed: just one chick, annually.

That’s sufficient for population recruitment for a species that can live for up to 60 years. But many don’t get to dance at all: the main challenge for shy albatross, Kim says, is “basically surviving until they can breed”. Many juveniles head west, to the southern Indian Ocean and the waters around South Africa, where they are often snared as bycatch in longline fishing operations.

after newsletter promotion

It’s a brutal way to die. Birds dive on the bait, only to be hooked like fish, dragged through the water and drowned. The situation is slowly improving, due to three countermeasures: setting the lines at night (when albatrosses don’t forage), weighting the hooks so the lines sink faster and tori lines, which use coloured streamers to create a visual barrier for the birds.

But global heating is the longer-term threat and that’s where we return to the story of Banyo Alfred – the exhausted albatross lucky enough to be picked up by the Twinnies.

Shy albatross are dutiful co-parents. While one partner forages at sea, the other guards the egg and chick, existing only on its fat reserves. Eggs are laid in September and hatch in December, with chicks leaving the nest in April. If one bird doesn’t come home, breeding is abandoned.

Which makes me wonder: assuming Alfie, an adult, was partnered (and a male), what happened to his mate and chick while he was in rehab? Famously monogamous, albatross divorce is on the rise, due to stress caused by warming waters, scarcer food supplies and more frequent storms.

I hate to think what kind of bad luck that would cause, so I’m throwing my support behind the shy albatross in the Guardian/Birdlife Australia 2025 bird of the year poll. Next winter, I urge you to head for your nearest headland, cast your eyes out to sea and remember the more hopeful words of Coleridge:

And a good south wind sprung up behind,

The albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariner’s hollo!

-

Andrew Stafford was a volunteer aboard the RSV Aurora Australis in the summers of 2004–05 and 2005–06, identifying and counting seabirds as part of a longitudinal population study

7 hours ago

5

7 hours ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·