PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by Adpathway

Reading the headline, you may justifiably say that this is a topic for a biology (or ornithology) book. And you would be right. So, this post will focus on individual chemicals that birds can smell, allowing me to take a chemical perspective and thus circumspect your assumed criticism.

Or as a military person might say, this is to avoid mission creep.

The chemical that gets the most attention from birds is dimethyl sulfide, or DMS, as its friends call it (not that it has many friends among humans – see the information below). It is the simplest thioether with just a methyl group on each side of the sulfur atom, and it has what Wikipedia tactfully describes as “a characteristic disagreeable odor”.

This chemical is particularly important for seabirds such as petrels and albatrosses, as its smell indicates the availability of food. Why? Here is the step-by-step explanation:

- Phytoplankton in the ocean produce dimethylsulfoniopropionate, another chemical, for a variety of reasons, including protection from oxidation

- When phytoplankton is eaten by zooplankton, the phytoplankton dies

- When it dies, it releases dimethylsulfoniopropionate

- The dimethylsulfoniopropionate gets converted to dimethylsulfide by enzymes that are part of bacteria or zooplankton

- Some of the dimethylsulfide evaporates from the water

- Seabirds smell the dimethylsulfide

Maybe that is not even the full explanation yet – as illustrated above, the DMS indicates the presence of zooplankton – and where there is zooplankton, there are bigger animals such as fish and squid, preying on the zooplankton. And that is what the seabirds are really after.

A very different bird species, Turkey Vultures, also uses the smell of volatile chemicals to find food. They are very sensitive to the smell of Dimethyl disulfide and Dimethyl trisulfide (and also Dimethyl sulfide), three closely related chemicals that are released soon when soft tissue decays.

Another chemical Turkey Vultures are attracted to is Ethyl mercaptan, which is the sulfur equivalent of ethanol (which most people just call alcohol) – probably also because it suggests decaying flesh.

This led to a side hustle of the vultures as indicators of gas leaks. In the 1970s and 1980s, utility companies in the United States noticed that Turkey Vultures were sometimes gathering along buried natural gas pipelines. Often, the locations where the vultures gathered were where the pipelines leaked. Obviously, the vultures were attracted by the ethyl mercaptan smell of the leaking gas, which they mistakenly took to indicate the presence of rotting flesh, while in reality, the smelly gas had just been added to the gas to warn humans of leaks. I am pretty sure the vultures felt kind of cheated.

Kiwis are different from vultures and seabirds, though they also strongly depend on their sense of smell to find food. However, their sense of smell is much more focused on their close proximity. And the molecules that they are attracted to are different as well.

Unfortunately, it is not even exactly clear which molecules are the most relevant for kiwis, but there are a few likely candidates:

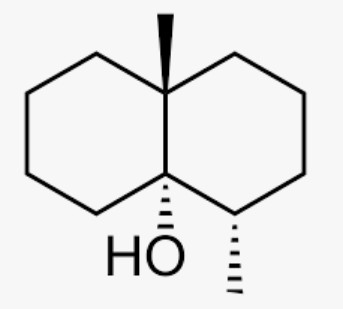

- Geosmin is produced by soil bacteria – it is responsible for the earthy smell after rain. Chemically speaking, it is a bicyclic alcohol with the somewhat complicated official name (4S,4aS,8aR)-4,8a-Dimethyloctahydronaphthalen-4a(2H)-ol. Many insects are attracted to its smell, as it may indicate the presence of microbial prey, which in turn may make it attractive to kiwis hunting for insects.

Geosmin

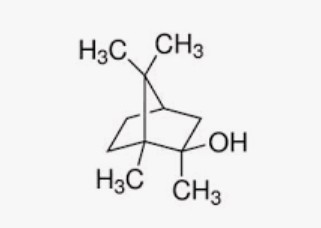

- 2-Methylisoborneol is an irregular monoterpene that is also produced by bacteria. Like geosmin, it attracts insects and springtails, again, potential food sources for kiwis.

2-Methylisoborneol

- Other volatile components, such as ammonia and low-molecular-weight amines and fatty acids, may indicate microbial activity next to kiwi prey.

Sources:

- Geosmin attracting insects

- Geosmin

- Olfaction in Turkey Vulture

- DMS as cue for seabirds

- Marine production and consumption of DMS and DMSP

Photo: Mjobling, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Written by Kai Pflug

Kai has lived in Shanghai for 21 years. He only started birding after moving to China, so he is far more familiar with Chinese birds than the ones back in his native Germany. As a birder, he considers himself strictly average and tries to make up for it with photography, which he shares on a separate website. Alas, most of the photos are pretty average as well.He hopes that few clients of his consulting firm—focused on China’s chemical industry—ever find this blog, as it might raise questions about his professional priorities. Much of his time is spent either editing posts for 10,000 Birds or cleaning the litter boxes of his numerous indoor cats. He occasionally considers writing a piece comparing the two activities.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·