PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

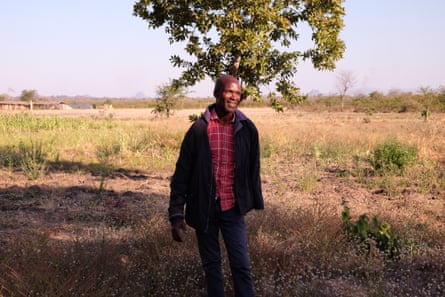

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayJulius Chibonda has moved twice in the past 16 months in search of enough water and fertile land to support his entrepreneurial dreams, one of millions of rural Malawians struggling with increasingly unpredictable rainfall and droughts made more ferocious by the climate crisis.

The 61-year-old farmer was eager to talk and quick to smile. But his face fell when he saw the dry, empty land in the village of Kampheko 2, where he had grown tomatoes, garlic, okra and maize.

“It hurts,” he said through an interpreter. “It’s a distressing sight because water is life. So without water nothing can exist.”

Malawi is the world’s fourth poorest country per capita, according to the World Bank, with an average annual income of just $508 in 2024. More than 80% of the population works in agriculture and 90% of farming uses just rain without irrigation, according to the World Food Programme.

That has made the landlocked southern African country particularly vulnerable to climate-fuelled disasters, including cyclones that have increased in intensity and frequency in recent years. In 2023, Cyclone Freddy killed more than 1,000 Malawians.

Since 2019, about 950,000 people have been displaced by cyclones, most temporarily, some multiple times. In a programme started in 2020, the government has helped 1,662 households (about 8,300 people) living in disaster-prone areas to relocate permanently, according to figures provided by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

The more gradual impacts of climate breakdown are also pushing people from their homes. Without concrete action, 216 million people worldwide could move internally by 2050 “due to slow-onset climate change impacts”, 86 million of them in sub-Saharan Africa, the World Bank estimated in 2021.

In 2023, African ministers signed a declaration on migration and the climate crisis, stating: “Migration can be a positive adaptation strategy if undertaken in a safe, orderly and regular manner.” But, it added that moving could exacerbate problems faced by already vulnerable groups.

The World Bank forecasts for gradual climate migration did not include estimates for Malawi. But during a devastating drought last year, 400,000 people moved within the country, according to IOM data.

Average temperatures in Malawi between 2015 and 2024 were 0.63 degrees higher than a century earlier, the World Bank data says. The rising population is also adding pressure – Malawi’s population has more than doubled to 21.6 million in 30 years.

Local officials reported more people moving from southern Malawi to the north and centre of the country, said Master Simoni, who works for the IOM in the country.

“As a result of the dry spells, we’ve seen that a lot of livelihood activities have been affected, be it farming, whether it’s crops or livestock, but also even casual labour,” he said.

In a swath of the Mangochi and Ntcheu districts south of Lake Malawi, mud-walled villages were scattered off dirt tracks, amid scrubby trees and dried-up riverbeds. Small-scale farmers spoke about depleted water supplies and falling crop yields. There were also many who had moved, some multiple times.

Chibonda moved to Kampheko 2 in 2021 to access land, as his home village had matrilineal inheritance. Granted 0.6 hectares (1.5 acres) by local chiefs who split Kampheko in two in 1982, he was attracted by the fertile soil and villagers growing rice, an especially thirsty crop.

Chibonda relied on a borehole but the irrigated radius around it started shrinking even in the three years he lived there. Then, the borehole was destroyed by vandals in 2024. Yellowed grass now pokes out the broken concrete.

On the other side of the village, at the bottom of a wide, dusty depression, 49-year-old Patricia Ngola scooped out dirty water from a hole populated by frogs and flies. Before 2020, the water hole could irrigate nearby fields, said the chief, John Sasamola.

Many Malawians struggle to access water for household needs, let alone agriculture. In rural areas 37% of people walk more than 30 minutes to get water, compared with 13% in towns and cities, according to Unicef.

In 2019, Unicef estimated $97m a year was needed to provide all Malawians with water within a half-hour walk by 2030 – the UN sustainable development goal (SDG) target year – with another $259m required annually for clean water in people’s homes.

after newsletter promotion

“Currently we are very far from that,” said Peter Phiri, Water Aid’s country director. In 2023, Unicef estimated spending had to quadruple to reach the SDG target. But, with recent US and other aid cuts, it could now be only one-sixth of the need, Phiri said.

Next to Kampheko 2’s dusty water hole, Steria Fakson harvested sweet potatoes by hand. The 0.4-hectare plot would yield just three bags, the 23-year-old said. Before she was born, it could produce enough to fill an oxcart, her step-grandmother Ngola told her. Fakson said she had not thought about moving, though: “I think I’ll wait for water.”

Not the entrepreneurial Chibonda. In June 2024, he trekked 15 miles to Chiganji. He had heard about available land near a borehole installed by Water Aid for a school, but now used by the whole village. A month later he brought his wife and four children, whose ages now range from two to seven, to the new site (Chibonda also had eight children with his late first wife).

However, villagers only allowed him to irrigate at night. That, and the meagre rainwater, still was not enough to fulfil Chibonda’s ambitions, which included creating fishponds.

“I look at water as capital for business … But as I started seeing that the water supply there was no longer going to support my dreams, I decided to move,” he said.

In January, Chibonda and his family migrated again. This time they moved 120 miles north-east to a 9 hectare (22 acre) plot, where water can be pumped from Lake Malawi about a mile away. Chibonda has planted sugarcane, bananas and cabbages and is targeting an orchard of 1,000 mango, orange and guava trees, as well as his much hankered-after fishponds.

“For me, it’s the rain patterns,” he said, reflecting on the impact of the climate crisis. “That is why my vision has always been to find a water source that doesn’t rely on rain … In recent years, at the time when we all need rain, the rain does not come.”

Gladys Khumbidzi first moved 22 years ago, because of repeated floods. Then, in her new home, the water supply got progressively worse. The shallow boreholes were drying up at the end of the November to April rainy season, sometimes as early as February. So, seven years ago, she moved again, to Chiganji.

But, recently, Khumbidzi has struggled to grow enough to feed herself and her three grandchildren, their home being a 25-minute walk from the water pump.

“In the first years, I could plant the vegetable gardens. But now … one year it will work, another year it will not work,” she said, recalling a year where the rain had not stopped – destroying her crops, and then last year, when the drought killed everything.

Khumbidzi, who is in her mid-60s , said she was too old to move again: “As the elders say, a rolling stone gathers no moss. I feel that I have rolled enough in my life. If I die, I will die right here.”

11 hours ago

13

11 hours ago

13

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·